The commentariat of Pushing Ahead of the Dame are dedicating February to listening to Bowie. Here are my thoughts on his dreaded Eighties and the promise of the early Nineties.

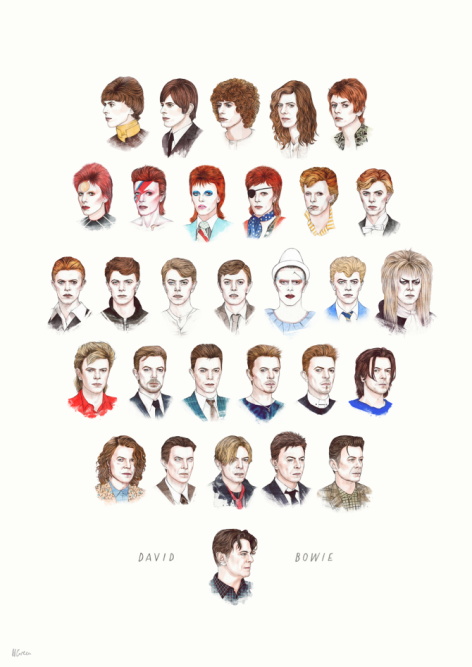

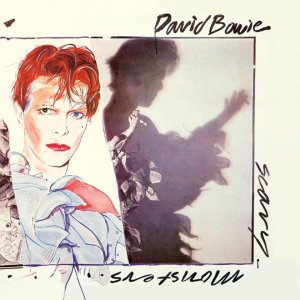

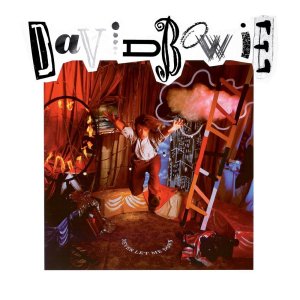

Other people had to wait until a few years of Reagan and Thatcher before declaring the Eighties miserable. Bowie got there first on a promotional disc for Scary Monsters, dismissing it as “awful” and “dreadful” as early as 1980, and prepared for the coming decade by making a collage of his past, throwing out old costumes. Tom Ewing, reviewing the standout “Ashes to Ashes”, remarked how his music was always strongest when it was just him in a hall of mirrors, and it’s while gazing at his distorted reflections that Bowie would write what critics consider his greatest last record (every new album he cut from the 90s onward seemed to come with a “best since Scary Monsters!” sticker on the packaging).

This is Bowie in peak art-rock period – living in New York, soaking up the punk and New Wave scene, giving an acclaimed performance in The Elephant Man, working with his best band and producer. Scary Monsters is him closing down the theatre and emptying it of props. Major Tom is back on Earth drugged out of his head. Lines and melodies reappear in new guises – “Rupert the Riley”‘s “beep-beep” hook ends up on “Fashion”, the Astronettes’ “I Am a Laser” gets fused in a transporter accident with “We Are Hungry Men” for “Scream Like a Baby”, the adolescent angst of “Tired of My Life” becomes sharper and far darker on “It’s No Game” (‘put a bullet in my brain / and it makes all the PAY-perrrrrs…‘; within months of recording this, John Lennon would be shot).

The British music scene had brought new contenders to the throne by way of the Blitz Club – Steve Strange, Spandau Ballet and Gary Numan amongst them – and while Bowie’s relinquishing the throne, he’s not going without a fight. Playing King Lear on the deranged “Teenage Wildlife”, he sneers at ‘broken-nosed moguls’, little more than the ‘same old thing in brand new drag’. He despairs at being crowded by his descendants, reduced to ‘a group of one’, and fills his vocals throughout the album with cracked grandeur – he’ll never sound this frenzied or regal or urgent again, and certainly not in his prime. You could see it as either harsh but well-meaning advice for the next generation, or a taunt from the grave, but the message is clear: “If you come for the king, you’d best not miss.”

The British music scene had brought new contenders to the throne by way of the Blitz Club – Steve Strange, Spandau Ballet and Gary Numan amongst them – and while Bowie’s relinquishing the throne, he’s not going without a fight. Playing King Lear on the deranged “Teenage Wildlife”, he sneers at ‘broken-nosed moguls’, little more than the ‘same old thing in brand new drag’. He despairs at being crowded by his descendants, reduced to ‘a group of one’, and fills his vocals throughout the album with cracked grandeur – he’ll never sound this frenzied or regal or urgent again, and certainly not in his prime. You could see it as either harsh but well-meaning advice for the next generation, or a taunt from the grave, but the message is clear: “If you come for the king, you’d best not miss.”

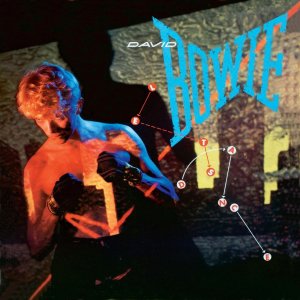

Scary Monsters‘ main problem, at least in terms of sequencing, is that it’s pretty top-heavy. The first side has the title track, “Up the Hill Backwards”, “Fashion” and “Ashes to Ashes”, while the second side (not bad by any stretch) has duds like “Because You’re Young” weighing it down, complete with indifferent windmill chords by Pete Townshend. This frontloading also haunts Let’s Dance, or “The One Where Bowie Makes All the Money”, but it’s more noticeable when the tracks aren’t as inspired. Having finally rid himself of his thieving manager and a hostile record label, Bowie recruits Nile Rodgers to write some hits. He gets a lemon meringue hairdo and a tan, calls his queerness a phase, and does a mammoth world tour that will slowly become the due thing for rock stars in the Eighties. Small wonder this is considered the definitive sell-out move.

But that seems a bit unfair. At its core, Let’s Dance borrows heavily from Fifties and Sixties R&B records, especially the ones from Bowie’s youth; his career started with fronting various R&B groups around Bromley and Beckenham. The blues-pop sound hadn’t yet become mainstream. At the time, too, Rodgers wasn’t known as a hitmaker – his last effort was on Debbie Harry’s doomed Koo Koo – and was perplexed when Bowie said it was what he did best. But then Bowie did have an eye for budding talent. In addition to cementing Rodgers’ skill as a producer with a tight sense of rhythm and time, Let’s Dance is jam-packed with guitar solos courtesy of future superstar Stevie Ray Vaughan, providing a musical foil for both the tightly-performed dance tracks and the vampiric iciness of Bowie’s vocals.

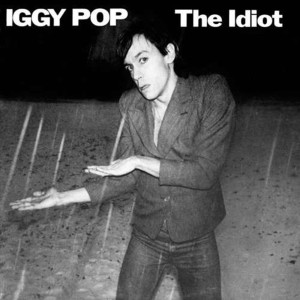

In the backhanded compliment to end all backhanded compliments, Paul Trynka describes Let’s Dance as “not a Great Album, but a Great Eighties Album”. Fatalistic songs get dressed up in shiny pop clothes, from the title track (‘for fear tonight is all…’) and the wonderful “Modern Love” to the slick Luciferian charm of the “China Girl” cover. Where Iggy was consumed with self-hatred, Bowie sells his wicked plans better. But there are clear signs he’s running out of steam. The bulk of the work was done by Rodgers and the session musicians, a good chunk of the tracks are covers, and a pointless remake of “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” that strips away all the Gothic melodrama of the original. “Ricochet” is the odd duck, and feels more like a promising student copying Bowie. I’d be lying if I said Let’s Dance didn’t make me dance, and it’s hard for me to really dislike, but it is very much the beginning of the end, Bowie happy to get lost at sea. The Imperial Phase stops here.

When I write these posts, I always refer to the notes I wrote while listening to these albums on Google Docs. Since I haven’t listened to some of these in full, the level of detail changes depending on my own familiarity. The one exception is 1984’s Tonight, where I had only one thing to say: “This is what plays in Patrick Bateman’s head.”

I could just leave it there and move onto the next one. I don’t think I can sum it up better. But I should explain my reasoning. Tonight is, by far and away, the worst David Bowie album I’ve ever heard. Considering some of the dreck I’m covering in this post, that’s no mean feat. What put this over the edge was that, for all the many many faults of the later years, you always got the sense he was trying. That he had some new ideas. There’s none of that in Tonight. It stinks of non-effort.

There are bright spots. “Blue Jean” is fun and disposable, while the opening track “Loving the Alien” has some potentially good ideas crippled by bad production. Everything else sounds like it should be playing on a cruise ship. White musicians performing reggae has a spotty precedent. On one side, you have The Police, and on the other, you’ve got Magic or – God help you – UB40. Bowie thought it would be a great idea to dabble in it right when everyone worthwhile was abandoning it. Why would you take a song about a girlfriend overdosing and turn it into a Club Med-lite duet with Tina Turner? I keep expecting the PA to come on midway through and announce they have shuffleboard on the Lido Deck.

There are bright spots. “Blue Jean” is fun and disposable, while the opening track “Loving the Alien” has some potentially good ideas crippled by bad production. Everything else sounds like it should be playing on a cruise ship. White musicians performing reggae has a spotty precedent. On one side, you have The Police, and on the other, you’ve got Magic or – God help you – UB40. Bowie thought it would be a great idea to dabble in it right when everyone worthwhile was abandoning it. Why would you take a song about a girlfriend overdosing and turn it into a Club Med-lite duet with Tina Turner? I keep expecting the PA to come on midway through and announce they have shuffleboard on the Lido Deck.

This is the sellout album if ever there was one, but I don’t even know if I can call it that. It reached #1, sure, but that was probably because it was a new Bowie album. Once people started listening, sales dipped sharply, and while EMI had already recouped their investment with Let’s Dance, they got second ideas about their new star player. I could go on and on about all the failings of this wretched, wretched album. Let’s just leave it there and move onto slightly less shit territory.

Popular wisdom is that Never Let Me Down is the true stinker of Bowie’s career. For a while, his official website didn’t list it; it just managed to make the Top Ten upon release; the accompanying Glass Spider Tour was widely pilloried for its overblown bombast and many, many technical failures. Having spent a good hundred words on Tonight, it won’t surprise you that I disagree, but Never Let Me Down is still pretty bad. I don’t think a better image sums it up than the cover – Bowie in a mullet jumping through a circus hoop.

While Let’s Dance at least sounds different to other Eighties records – I’d argue it has a lot in common at least musically and thematically with Thriller – Never Let Me Down is very much of the time. “Busy” almost sells it short. Even the promising cuts, like “Zeroes”, the title track and the superb “Time Will Crawl”, are overproduced and loaded with geegaws that don’t give them room to breathe. Def Leppard drums, whole armies of backing vocalists, waves of synthesisers, horn sections, endless guitar wankery from Peter Frampton…the kitchen sink probably has a credit somewhere.

Tonight‘s problem is that Bowie very clearly didn’t care about what he was selling, but you couldn’t accuse him of that on Never Let Me Down. On the contrary, he tries way too fucking hard. Some of the vocal melodies are so complicated that Bowie sounds strained and out-of-breath trying to sing them. Not helping is that a lot of the songs are, frankly, not very inspired. “New York’s In Love” sounds like it was commissioned by NYC & Company to attract the world’s most boring tourists. “Day-In Day-Out” is a musical poverty safari. Mickey Rourke has a mumbled John Cooper Clarke-esque rap on “Shining Star (Makin’ My Love)”, and it’s somehow not the worst part of the song. Someone as talented and forward-thinking as Bowie spending so much time, money and effort on tepid corporate rock is like a team of Nobel-winning chemists working round-the-clock to make a new brand of stool softener.

In pre-release interviews, Bowie was enthusiastically talking up the album, how pleased he was and how much fun he had on tour. Part of it might just be letting himself get browbeaten by popular consensus, but Never Let Me Down failing as publicly as he did really seemed to shock him. The overproduction is the album’s biggest sin – “Time Will Crawl” got remixed to great effect in 2008, and I’d like to see someone like James Murphy or Richard X take a stab at salvaging it. For now, though, Bowie’s powers were failing him. He needed a fresh start. He found it in the form of his press officer’s husband.

In pre-release interviews, Bowie was enthusiastically talking up the album, how pleased he was and how much fun he had on tour. Part of it might just be letting himself get browbeaten by popular consensus, but Never Let Me Down failing as publicly as he did really seemed to shock him. The overproduction is the album’s biggest sin – “Time Will Crawl” got remixed to great effect in 2008, and I’d like to see someone like James Murphy or Richard X take a stab at salvaging it. For now, though, Bowie’s powers were failing him. He needed a fresh start. He found it in the form of his press officer’s husband.

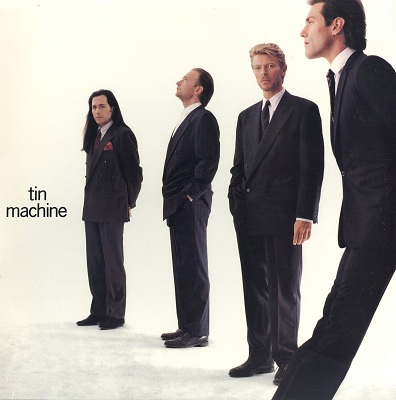

Reeves Gabrels is the most controversial of Bowie collaborators, from his elaborate guitar squawking to his in-your-face and boldly confrontational approach, which seemed at odds with his rather ordinary appearance. Depending on the year, he looked like a retired History of Art professor or your dad in a Rocky Horror tribute act (nowadays he looks like an owl that used to be a Hell’s Angel). But he is absolutely vital to the Bowie he knew today. A friend and confidant during the Glass Spider Tour, he would listen to Bowie complain about how he felt compelled to make this music; Gabrels asked, not unreasonably, why he needed to do this. He was David Bowie, for God’s sake. His best music has always been when he was at his most selfish – not uncaring, necessarily, but defiant and bold. This was exactly what Bowie needed to hear, and after years of constantly turning right with everyone else, now he was leaving the race and going left.

Not a lot of people were happy with the results, though. Bowie recruited two old figures from his past – the Sales brothers, Tony and Hunt – to play with him and Gabrels on a few sessions. Somehow they ended up in a band they would call Tin Machine, although it’s probably more accurate to say they were two teams who shared one office. Bowie and Gabrels were artsy-minded and avant-garde, determined to push rock music out of its ossified state; the Sales brothers were experienced session men with punk backgrounds and played with demonic ferocity, with Hunt playing his drums on a twenty-foot high riser. All four were talented musicians with huge personalities, none of them prepared to be sidemen, all wanting to give popular music a shot in the arm. Tin Machine’s recording process is borderline straight-edge: no synthesisers, no overdubs, no rewrites, everything cut live, with a sound influenced by Hendrix, Glenn Branca and upcoming Massachusetts band Pixies.

All of this makes for interesting reading, but in practice, the Machine failed to execute the grand vision in Bowie’s head. As part of the schedule, I listened to both Tin Machine albums back-to-back – 1989’s Tin Machine and the 1991 sequel Tin Machine II – and I came away wanting to go to sleep. In pieces, it’s fine, even inspired at points. “Prisoner of Love” builds and builds to the point it gets vertiginous, and “I Can’t Read” almost singlehandedly justifies the project; there, the tension between a frontman pining for his muse while his band storms away uncaring drives it forward. But at album length, it’s exhausting to listen to. It’s like eating a dinner made entirely of M&Ms piece-by-piece.

All of this makes for interesting reading, but in practice, the Machine failed to execute the grand vision in Bowie’s head. As part of the schedule, I listened to both Tin Machine albums back-to-back – 1989’s Tin Machine and the 1991 sequel Tin Machine II – and I came away wanting to go to sleep. In pieces, it’s fine, even inspired at points. “Prisoner of Love” builds and builds to the point it gets vertiginous, and “I Can’t Read” almost singlehandedly justifies the project; there, the tension between a frontman pining for his muse while his band storms away uncaring drives it forward. But at album length, it’s exhausting to listen to. It’s like eating a dinner made entirely of M&Ms piece-by-piece.

While the players had a mutual goal, their ways of going about it were radically different. Bowie has never been comfortable being a full-on macho rocker, and a lot of his songs require finesse in a way that Tin Machine just does not provide. “Heaven’s On Here” has one of his best vocals in years, but the last two minutes are spent on a pissing contest between Gabrels and Hunt to see who can solo the longest. “Working Class Hero” and “If There Is Something” get stripped of their irony and wit because all the Machine know how to do is pummel a track into submission. Socially-Conscious Bowie rears his ugly head on “Crack City” and “Under the God”, blunt-force tracks with easy targets (drugs and Neo-Nazism respectively).

Nick Cave’s Grinderman, another project designed as a deck-clearing exercise, succeeded where Tin Machine failed, and I wonder if it’s because Cave can sell that low-fi grimy blues sound better than an aesthete like Bowie. There’s a solid, potentially great album in these two releases, especially since TMII is more melodic at points than its predecessor. The final track on a Tin Machine record, “Goodbye Mr Ed”, is one hell of a high note for a band to finish on, and they stirred something in Bowie. This was a band full of players who challenged him at every turn. For all of his ego, Bowie listened to advice and wasn’t afraid to shift direction if it was more advantageous to do so. It made him fearless, and that’s what the world needed.

Nick Cave’s Grinderman, another project designed as a deck-clearing exercise, succeeded where Tin Machine failed, and I wonder if it’s because Cave can sell that low-fi grimy blues sound better than an aesthete like Bowie. There’s a solid, potentially great album in these two releases, especially since TMII is more melodic at points than its predecessor. The final track on a Tin Machine record, “Goodbye Mr Ed”, is one hell of a high note for a band to finish on, and they stirred something in Bowie. This was a band full of players who challenged him at every turn. For all of his ego, Bowie listened to advice and wasn’t afraid to shift direction if it was more advantageous to do so. It made him fearless, and that’s what the world needed.

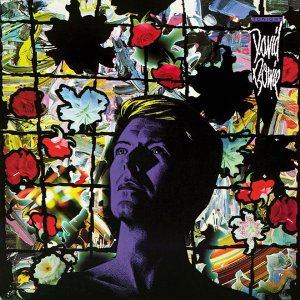

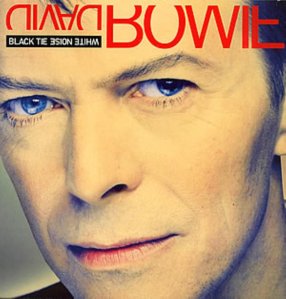

For a while, the dominant memory I had of Black Tie White Noise, the official comeback record after the indulgence of Tin Machine, was that it cost me £1.03 to complete it on iTunes, having bought a few of the songs beforehand. The last Bowie album to top the UK charts for twenty years, it was a modest seller that made little impact and failed to re-establish him as a powerhouse. On another listen, though, BTWN is better than I remember – not great, but some of these tracks have grown on me, especially the instrumentals (“The Wedding” is lovely, even when it has glurgy but strangely heartwarming lyrics pasted onto it, and “Looking for Lester” is indescribably cool).

Nile Rodgers is producing again, but he wasn’t running the show like he did on Let’s Dance. There’s a weird game Bowie’s playing on here – it’s his first solo album in six years, but there’s no obvious hit single, and there’s all these weird flourishes like Middle Eastern instruments and jazz stylings that stop it from being commercial. The theme is right there in the title; it’s an album about ties and bonds. His marriage to Iman is the most obvious, and there are ties to his past – Mick Ronson returns for one last solo on “I Feel Free”, he duets with childhood hero Lester Bowie on “Looking for Lester”, Terry Burns is given a futuristic wake on the excellent “Jump They Say” – but there’s also the artists he’s influenced. Sometimes this works, like his cover of Scott Walker’s “Nite Flights”, a song that wouldn’t have been possible without the Berlin albums; other times it doesn’t, like the glittering camp spectacle of Morrissey’s “I Know It’s Gonna Happen Someday”, festooned with live instruments on an electronic-influenced album.

Even with his creative batteries recharged, it’s clear Bowie wasn’t yet all there. “Don’t Let Me Down and Down” is like the wretched Eighties never left, now complete with awful cod-Caribbean accent, and there’s no greater act of misplaced generosity than giving the bulk of the title track to a complete non-entity like Al B. Sure!. Not that Bowie doing it on his own would have made it better, mind; the plastic soul of Young Americans had more to say than this watery knock-off of “Ebony and Ivory”.

Even with his creative batteries recharged, it’s clear Bowie wasn’t yet all there. “Don’t Let Me Down and Down” is like the wretched Eighties never left, now complete with awful cod-Caribbean accent, and there’s no greater act of misplaced generosity than giving the bulk of the title track to a complete non-entity like Al B. Sure!. Not that Bowie doing it on his own would have made it better, mind; the plastic soul of Young Americans had more to say than this watery knock-off of “Ebony and Ivory”.

But, then again, you listen to Bowie for the weird shit, don’t you? That’s the appeal, and there are more winners on BTWN than losers. “Pallas Athena”, the sound of Philip Glass going to the club, appears to have inspired Rob Dougan’s entire career. It’s neither fish nor fowl, and I’ll always have a place in my heart for weird orphans like this. Fortunately, Bowie didn’t feel the need to be a commercial superstar any more. The record still sold, and now that he was free from having to tour it, he could move onto whatever interested him next.

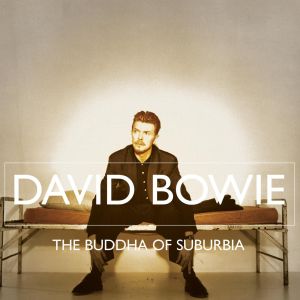

The Buddha of Suburbia is the forgotten Bowie album. At the time of its release, it was classified as a soundtrack for the BBC series of the same name rather than a proper studio record, despite using basically no music from the show itself. The original novel by Hanif Kureishi is almost a stealth biography of him – a queer young man escaping Bromley to make something of himself in London – while a picture of Bowie at the protagonist’s high school is treated like a holy relic. So Bowie and his jack-of-all-trades Erdal Kizilcay, the one-man band, set about turning Buddha into a musical autobiography.

Not the kind you’d expect, though. Rather than pastiches of his previous work, Buddha is based more on abstract impressions. Jazz, Philip Glass, glam rock and Brian Eno get thrown into the mix, but blurred and distorted radically. “Ian Fish, UK Heir” in particular is a palimpsest of a song; the title track scraped away of everything but the most basic notations. In the liner notes, Bowie writes about the narrative form being a ball-and-chain holding music back as an art form; this is the closest he’s gotten to writing ambient music, but infused with jazz and electronic music.

Bowie called Buddha his favourite album, continuing his reign as King Hipster by choosing the least-known entry in his discography. It’s also where the creative energies really begin to work again in the old bastard; it’s practically a font of new and bold ideas. “Bleed Like a Craze, Dad” seems to mutate and bubble over with every fresh element introduced. There are traces of Twin Peaks in the beautiful “The Mysteries”, and there’s a fantastic one-two punch of “Strangers When We Meet” and “Dead Against It”. I don’t quite know what it is about those two tracks, but listening to them fills me with joy. The book and show are focused on change, on adapting to other cultures while retaining your own identity. That’s a very Bowie notion, and Buddha of Suburbia is when he finally recaptured the lightning.

Bowie called Buddha his favourite album, continuing his reign as King Hipster by choosing the least-known entry in his discography. It’s also where the creative energies really begin to work again in the old bastard; it’s practically a font of new and bold ideas. “Bleed Like a Craze, Dad” seems to mutate and bubble over with every fresh element introduced. There are traces of Twin Peaks in the beautiful “The Mysteries”, and there’s a fantastic one-two punch of “Strangers When We Meet” and “Dead Against It”. I don’t quite know what it is about those two tracks, but listening to them fills me with joy. The book and show are focused on change, on adapting to other cultures while retaining your own identity. That’s a very Bowie notion, and Buddha of Suburbia is when he finally recaptured the lightning.

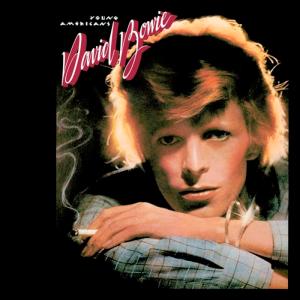

Calling it plastic also belies the fact that there’s real goddamn soul on this record. Bowie might have just been wearing a gouster’s clothes but damn if he couldn’t act the part, although having an amazing supporting cast (ex-James Brown man Carlos Alomar, backing singers including a young Luther Vandross) undoubtedly helped. When recording in Sigma Studios, he was horrified by the sound of his voice; where other studios had effects that could cushion the blow, Sigma was “dry”, so having a great backing band only pushed him further. He would be a worthy singer for the players, and the proof is in the gorgeous and soulful “Win”.

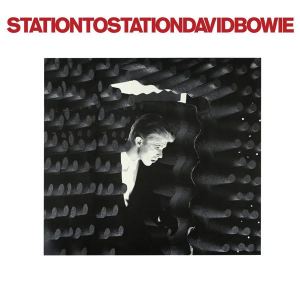

Calling it plastic also belies the fact that there’s real goddamn soul on this record. Bowie might have just been wearing a gouster’s clothes but damn if he couldn’t act the part, although having an amazing supporting cast (ex-James Brown man Carlos Alomar, backing singers including a young Luther Vandross) undoubtedly helped. When recording in Sigma Studios, he was horrified by the sound of his voice; where other studios had effects that could cushion the blow, Sigma was “dry”, so having a great backing band only pushed him further. He would be a worthy singer for the players, and the proof is in the gorgeous and soulful “Win”. Station to Station is Bowie’s first attempt at marrying R&B with krautrock, crafting neat minimalist lines and charging them with life. For all the Duke’s iciness, there are heart-stopping moments: desperate negotiations with God on “Word on a Wing”, the slick flattery of “Golden Years” transforming into pleading, and the decadent croon of “Wild is the Wind”, elevating an abstract song dashed off for a movie into pure art. Hybridisation seems to be the name of the game here. “TVC15” merges a 1950s teenage death ballad with the Ballardian idea of television as an all-consuming predator we willingly allow into our homes. Christianity is used interchangeably with the Kabbalah and Gnosticism and Aleister Crowley; English Pagans would throw random gods together if it would help them get through the day. Past and future, white and black magic, America and Europe – all colliding together, with Bowie harnessing the resultant energy. Transitional record? Sure, but it stands on its own, self-assured and manically confident.

Station to Station is Bowie’s first attempt at marrying R&B with krautrock, crafting neat minimalist lines and charging them with life. For all the Duke’s iciness, there are heart-stopping moments: desperate negotiations with God on “Word on a Wing”, the slick flattery of “Golden Years” transforming into pleading, and the decadent croon of “Wild is the Wind”, elevating an abstract song dashed off for a movie into pure art. Hybridisation seems to be the name of the game here. “TVC15” merges a 1950s teenage death ballad with the Ballardian idea of television as an all-consuming predator we willingly allow into our homes. Christianity is used interchangeably with the Kabbalah and Gnosticism and Aleister Crowley; English Pagans would throw random gods together if it would help them get through the day. Past and future, white and black magic, America and Europe – all colliding together, with Bowie harnessing the resultant energy. Transitional record? Sure, but it stands on its own, self-assured and manically confident.

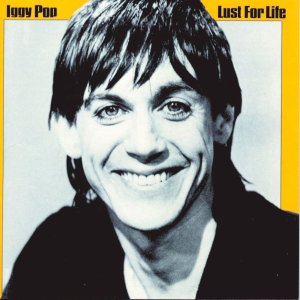

Largely free of the murk from the last album, Lust for Life is full of energy. The first thing you hear is Hunt Sales beating out a Motown tattoo as though his drums did him wrong; the eponymous “Lust for Life” builds from there, growing in momentum and delirious joy that it found its calling nearly twenty years later as the theme for Trainspotting (and also for Royal Caribbean commercials). The whole album is a hoot, especially “Success”, where Iggy plays Southern Baptist preacher and challenges his backing singers to keep up with him, and “Tonight”, a dark joke of a song that’s a sincere declaration of love to his girlfriend overdosing on the floor. Lust for Life can’t quite sustain the momentum – the Jim Morrison cabaret of “True Blue” and chest-puffing bravado of “Neighborhood Threat” drag too long compared to the sprightliness of the first side – but everyone involved’s working at the height of their powers, and there are two perfect rock songs on there: the title track, and “The Passenger”, the sunnier side of “Nightclubbing” in that it makes prowling the city by night sound Zen.

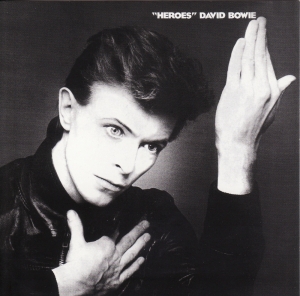

Largely free of the murk from the last album, Lust for Life is full of energy. The first thing you hear is Hunt Sales beating out a Motown tattoo as though his drums did him wrong; the eponymous “Lust for Life” builds from there, growing in momentum and delirious joy that it found its calling nearly twenty years later as the theme for Trainspotting (and also for Royal Caribbean commercials). The whole album is a hoot, especially “Success”, where Iggy plays Southern Baptist preacher and challenges his backing singers to keep up with him, and “Tonight”, a dark joke of a song that’s a sincere declaration of love to his girlfriend overdosing on the floor. Lust for Life can’t quite sustain the momentum – the Jim Morrison cabaret of “True Blue” and chest-puffing bravado of “Neighborhood Threat” drag too long compared to the sprightliness of the first side – but everyone involved’s working at the height of their powers, and there are two perfect rock songs on there: the title track, and “The Passenger”, the sunnier side of “Nightclubbing” in that it makes prowling the city by night sound Zen. In a way, it’s the antithesis to Blackstar. Where that record has an avant-garde jazz group translating rock music into their own language, “Heroes” has a rock band (Robert Fripp plus the Alomar-Murray-Davis trio) taking a stab at making free jazz. The increased use of Oblique Strategies, a way of breaking creative blocks, led to more improvisation, with most of the music coming from jam sessions. It’s a looser, more confident sound, even with the tropical extremes in mood throughout. You go from the eerie “Neukoln”, full of Bowie skronking away on his sax, to the deliriously camp “The Secret Life of Arabia”. Where Low is probably about depression, “Heroes” is more bipolar, the songs mutating – “Blackout” drops away for Davis to drum up a storm amidst shrieks for a doctor, “Joe the Lion” sees Bowie go from a newsreader-like delivery to pure manic savagery.

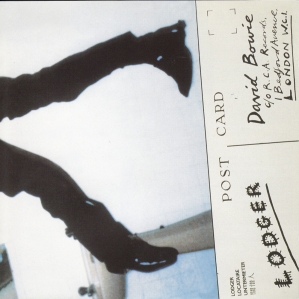

In a way, it’s the antithesis to Blackstar. Where that record has an avant-garde jazz group translating rock music into their own language, “Heroes” has a rock band (Robert Fripp plus the Alomar-Murray-Davis trio) taking a stab at making free jazz. The increased use of Oblique Strategies, a way of breaking creative blocks, led to more improvisation, with most of the music coming from jam sessions. It’s a looser, more confident sound, even with the tropical extremes in mood throughout. You go from the eerie “Neukoln”, full of Bowie skronking away on his sax, to the deliriously camp “The Secret Life of Arabia”. Where Low is probably about depression, “Heroes” is more bipolar, the songs mutating – “Blackout” drops away for Davis to drum up a storm amidst shrieks for a doctor, “Joe the Lion” sees Bowie go from a newsreader-like delivery to pure manic savagery. No, I’d say that this is an album built from salvage material, kind of like Diamond Dogs. Where that was built on failed narratives and ideas, however, Lodger‘s foundation is in a more recognisably human realm. This is Bowie as tourist, an alien on safari, re-engaging with the rest of us. We get songs about living with depression, drunken German mercenaries, Turkish workers, queer men, women abused by men, the record-buying public (Bowie records, to be precise: “DJ” can mean disc jockey or David Jones, remember). Even the angel of death, on the Wildean melodrama of “Look Back in Anger”, has a cough and wings that have seen better days.

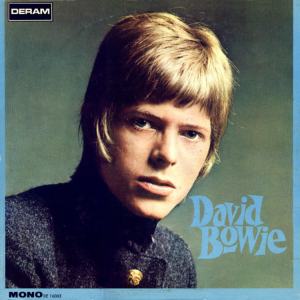

No, I’d say that this is an album built from salvage material, kind of like Diamond Dogs. Where that was built on failed narratives and ideas, however, Lodger‘s foundation is in a more recognisably human realm. This is Bowie as tourist, an alien on safari, re-engaging with the rest of us. We get songs about living with depression, drunken German mercenaries, Turkish workers, queer men, women abused by men, the record-buying public (Bowie records, to be precise: “DJ” can mean disc jockey or David Jones, remember). Even the angel of death, on the Wildean melodrama of “Look Back in Anger”, has a cough and wings that have seen better days. of his pre-fame years, more a glorified audition tape where a nineteen-year old Bowie puts on a variety of hats to see which one looks the best, bordering on novelty. You can almost hear the strain at points –

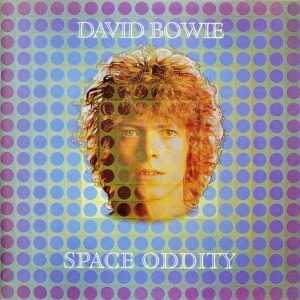

of his pre-fame years, more a glorified audition tape where a nineteen-year old Bowie puts on a variety of hats to see which one looks the best, bordering on novelty. You can almost hear the strain at points –  ll intents and purpose, the narrative starts with the folkie phase, with Bowie in the role of a serious young singer-songwriter who got lucky with a one-off novelty and determined to show he’s no flash in the pan. So 1969’s David Bowie is full of songs tracking at around five minutes each, even when

ll intents and purpose, the narrative starts with the folkie phase, with Bowie in the role of a serious young singer-songwriter who got lucky with a one-off novelty and determined to show he’s no flash in the pan. So 1969’s David Bowie is full of songs tracking at around five minutes each, even when

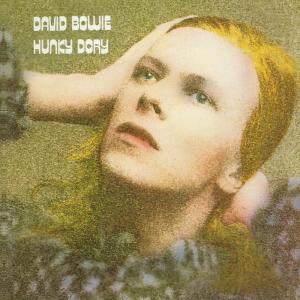

Hunky Dory deals with legacy and succession: “Oh! You Pretty Things” quietly accepts that a new generation is coming along; “Kooks” was written after finding out he was a father. But the second side is more overtly about his influences, in some cases cheekily positioning himself as an heir apparent –

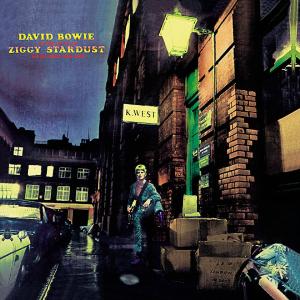

Hunky Dory deals with legacy and succession: “Oh! You Pretty Things” quietly accepts that a new generation is coming along; “Kooks” was written after finding out he was a father. But the second side is more overtly about his influences, in some cases cheekily positioning himself as an heir apparent –  I’d thought I had run out of new things to say about Ziggy Stardust, but listening to it again has unearthed new gems. If you cut

I’d thought I had run out of new things to say about Ziggy Stardust, but listening to it again has unearthed new gems. If you cut

Some of the interpretations are even inspired –

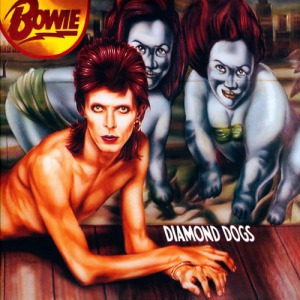

Some of the interpretations are even inspired –  with Burroughs surprised that Bowie hadn’t read The Waste Land. That must have stuck in his head, because Diamond Dogs tries to do for rock music what Eliot did for mythology. Cut it down the middle and you’ll find Ballard, Orwell, vaudeville, John Rechy, Joe Meek, the Stones, Tod Browning’s Freaks and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. And those are just the ones I can name off the top of my head. It’s a record made from junk and debris.

with Burroughs surprised that Bowie hadn’t read The Waste Land. That must have stuck in his head, because Diamond Dogs tries to do for rock music what Eliot did for mythology. Cut it down the middle and you’ll find Ballard, Orwell, vaudeville, John Rechy, Joe Meek, the Stones, Tod Browning’s Freaks and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. And those are just the ones I can name off the top of my head. It’s a record made from junk and debris.